U.S. Shale Is Growing Old. That’s a Problem for Donald Trump’s Oil Plans

Disciplined crude giants have replaced the unruly band of frackers who led the shale boom

The Wall Street Journal: U.S. Shale Is Growing Old. That’s a Problem for Donald Trump’s Oil Plans. (December 28, 2024)

President-elect Donald Trump wants U.S. oil producers to rekindle their once-frenzied drilling, but the country’s shale patch has changed since his first administration.

Wildcatters are mostly gone, replaced by more disciplined oil giants. Wall Street has helped instill that discipline, pushing oil companies to focus more on producing cash for investors. Meanwhile, production in most U.S. crude regions is set to decline as fields mature and sweet spots dwindle. What this means: The oil patch is unlikely to see the kind of breakneck growth it saw in Trump’s first term, when daily crude production shot up from about nine million barrels to roughly 13 million.

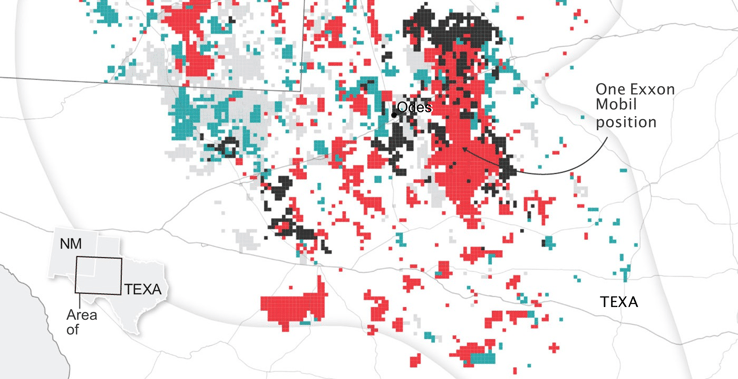

“We’re not going to have the explosive growth that we’ve seen,” Richard Dealy, who oversees Exxon Mobil’s Permian operations, said. Earlier this year, Exxon acquired rival Pioneer and its vast production for $60 billion. The company said earlier in December it aims to roughly double its production in the Permian Basin to about 2.3 million barrels of oil equivalent a day by 2030.

Note: Areas where company-owned land did not exceed 50% of the total area are not shaded. Sources: Enverus (oil positions); Energy Information Administration (Permian Basin) Carl Churchill/WSJ

Disappearing wildcatters

The changes are reshaping the Permian Basin of West Texas and New Mexico, the largest oil field in the U.S. A decade ago, 30 companies produced about a third of the crude there. As of July, Exxon, Diamondback Energy and Occidental Petroleum cranked out a similar share of the basin’s output.

A telltale sign of shale’s ripening is the fates of rapidly disappearing wildcatters, who ignited the shale boom by deploying new drilling techniques and hydraulic fracturing. These companies, many of them privately held, retained a penchant for frantic drilling even after their publicly traded peers reined in spending and started returning cash to investors.

When crude prices rebounded from the pandemic depths, private outfits such as Endeavor Energy Resources were among the first to slowly step up production. Since then, public companies have gobbled up many of these private firms, including Endeavor, which Diamondback bought for $26 billion this year.

Private firms today run about 25% of rigs in the Permian, down from roughly 50% in January 2022, said Rob Wilson, an analyst with energy analytics firm East Daley Analytics. This decline means much fewer companies are willing—or able—to dial up supply when prices creep higher.

Drill down

The number of active U.S. shale companies has declined in part because bigger companies acqui frackers.

Note: Gross oil production; data is for July 2014 and July 2024 Source: Novi Labs

Despite a flurry of mergers in the past year and a half, shale remains far less concentrated than the auto or airline industries, and investors believe that it will see more megadeals.

“As it consolidates further, it becomes a giant factory,” Chris Atherton, chief executive of EnergyNet, a marketplace for oil and gas assets, said of the Permian.

Efficiency over growth

After rebounding from the pandemic-induced bust, drillers pushed U.S. production to a record of over 13 million barrels a day under President Biden. Though oil prices remain high enough for many producers to make a profit, drillers are running into geologic limits that will constrain further growth—barring any technological breakthrough—keeping drilling rigs idle.

Operators are also wrestling with limited capacity from the power grid to support their electricity-intensive activity, and struggling to dispose of the huge amounts of wastewater they produce alongside crude.

Note: Monthly averages as of November Sources: Enverus (oil rig count); Thomson Reuters (WTI crude prices) Carl Churchill/WSJ

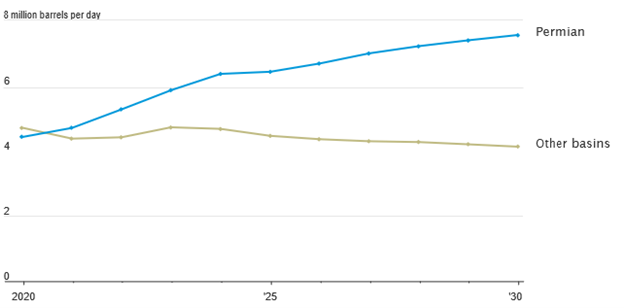

Other basins that powered the shale revolution have either seen declining output or are set to roll over, according to analysts at JPMorgan Chase. This includes the Eagle Ford Shale in Texas, the Williston Basin in North Dakota and the DJ Basin in Colorado.

JPMorgan estimates that U.S. crude oil production will grow by 3.6% between now and the end of the decade to reach about 13.5 million barrels a day. That compares to a roughly 13.4% increase in output since 2022.

Oil production is declining in most onshore basins outside the Permian

Source: JPMorgan estimates, Enverus

Instead of additional drilling, companies are focused on squeezing more oil out of what remains.

“We’ve been drilling 300 wells a year here for, you know, eight years. We better get better at what we do,” Diamondback President Kaes Van’t Hof said.

The industry’s rising productivity means that companies can do more with fewer employees. Many executives expect the industry to contract further.

U.S. oil and gas extraction jobs

Note: Average per year Source: Labor Department