Be Prepared to Keep Paying More for Electricity

Data centers are getting much of the blame lately for rising power costs, but they aren’t the only catalyst.

Read the article from the Wall Street Journal

Most Americans are paying more for electricity—and need to prepare their wallets for further pain ahead.

Data centers are getting much of the blame lately for rising power costs, but they aren’t the only catalyst and don’t always cause increases. The reasons our bills are rising are complex and varied. Hurricanes, wildfires, state renewable-energy plans and the replacement of aging or damaged grid equipment are all playing a role.

Discontent over rising power bills has become a hot political issue that is expected to spill into the 2026 midterm elections.

“I do think that we’re entering a new era, a new politics of electricity,” said Charles Hua, executive director of PowerLines, a nonprofit that advocates for utility customers.

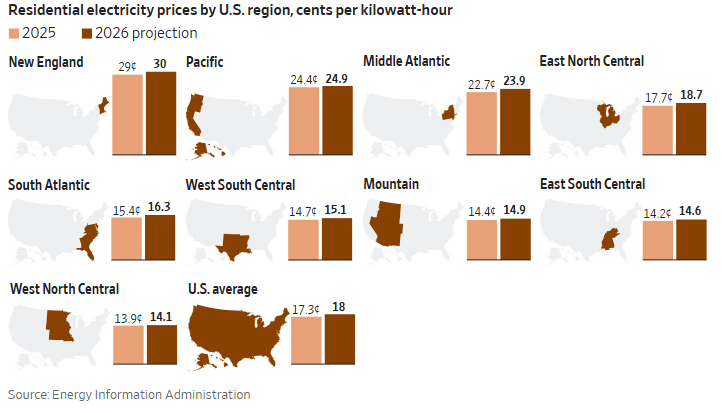

The Energy Department expects the U.S. average residential electricity rate to rise around 4% next year following a 4.9% increase in 2025. Spending on power is usually the second-biggest energy-related expense for consumers after gasoline.

Liliana Olayo, a 51-year-old retail worker in Aurora, Ill., has been playing catch-up since the summer, when her electricity bills rose to $300 to $400 a month, up from about $200 previously in the summer. Her latest bill was $454, which includes past-due amounts.

Olayo has been working 11-hour shifts to earn enough money to pay off the bill as winter heating costs loom. She skipped putting Christmas lights on her house and said neighbors have done the same.

“I’m not the only one,” Olayo said. “It’s beautiful, but it’s a luxury right now.”

The cost of electricity generally has moved higher with inflation, but it began outstripping other cost increases in 2022, when natural-gas prices soared after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

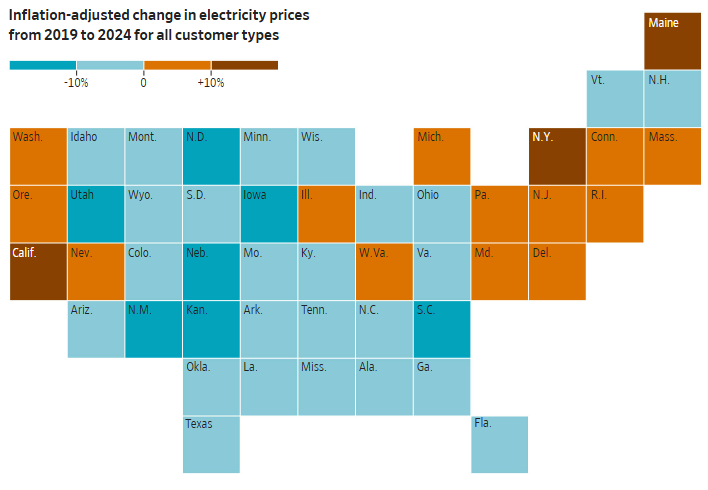

Outsize price shocks haven’t been universal. Customers in most U.S. states saw electricity-price increases that were lower than inflation from 2019 to 2024, according to a study led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

In some states, the arrival of new customers, such as data centers, helped keep prices lower than they would have been otherwise.

The recent price trend, though, is generally up.

Electricity prices played a pivotal role in the New Jersey governor’s race this past fall. Democrat Mikie Sherrill, who prevailed, called for freezing rates, though such a move would be complex. Garden State residential rates climbed 21% in September from the previous year, according to the Energy Department.

In Georgia, voter anger over rate increases was a factor that helped two Democrats unseat Republican incumbents on the state’s utility commission.

Power bills include the costs of generating electricity and delivering it by high-voltage transmission lines and distribution lines in cities. Regulation regarding pricing typically happens at the state level.

Shifting factors such as fuel prices and temperatures affect customer bills, and so do storms and wildfires that damage infrastructure.

This winter, for instance, home-heating costs are projected to jump 9% to about $995 for the season running from November to March. That is up from a year earlier owing to colder-than-usual weather and rising natural-gas and electricity prices, according to the National Energy Assistance Directors’ Association.

As for infrastructure, investor-owned utilities are projected to invest $1.1 trillion in transmission and distribution systems, generation, and gas-delivery lines between 2025 and 2029, twice as much as they spent in the previous 10 years, according to Edison Electric Institute, a utility trade group. Costs are typically approved by regulators and recovered from various types of customers over time.

Next year, regions projected to see at least a 5% rate increase include a swath of the East Coast from New York to Florida, along with other states from Wisconsin and Illinois to West Virginia, according to the Energy Department.

The average U.S. residential electricity rate has been climbing less than 1 cent a kilowatt-hour in recent years. It is expected to average 17.3 cents this year and 18 cents next year, the agency predicts.

Customers across the country are expected to see electricity-rate increases in 2026.

“We’re in a period of general inflation and rate rise, and that’s just attracting a lot of attention and getting a lot of pushback by regulators that are intent on keeping energy costs low,” said Jim McMahon, head of the energy practice at Charles River Associates, a consulting firm.

Nationally, power prices climbed 23% between 2019 and 2024, according to the Lawrence Berkeley-led study. When adjusted for inflation, though, rates were mostly flat.

An exception was in 2022, the year of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. New England was especially hard-hit as natural-gas prices surged.

Residential customers in California felt the most pain over the period of the study: an inflation-adjusted price increase of 35%. Wildfire mitigation and insurance was the biggest contributor. Another was the rooftop-solar and utility credits offered to homeowners for the electricity they added to the grid. That shifted more system costs to other customers.

State renewable-energy mandates mostly boosted costs, especially across the Middle Atlantic and the Northeast, where solar and wind quality are relatively poor, the study found. In states without mandates, the study found no “obvious relationship” between retail electricity rates and renewables.

Maine was hit hard by winter storms and Florida by hurricanes, leading to repair costs.

In North Dakota, residential rates fell on an inflation-adjusted basis. Cryptocurrency companies, data centers and oil-and-gas projects were connected to the grid and helped spread costs over a greater volume of electricity sales.

Drew Maloney, chief executive of Edison Electric Institute, said the industry is trying to emphasize that inflation-adjusted prices aren’t rising everywhere.

“Data centers aren’t driving the cost,” he said. “A lot of times it’s the state policies that are driving the cost.”

One exception is the PJM Interconnection, a regional transmission organization in the Middle Atlantic and the Midwest, where electricity supplies are tightening, the study said. The area has a large concentration of data centers, and power bills started to increase this past summer.